Lesson 12: Version control with Git¶

(c) 2018 Justin Bois. With the exception of pasted graphics, where the source is noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0. All code contained herein is licensed under an MIT license.

Parts of this lesson are based on a similar lesson from Software Carpentry, itself also licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0.

This document was prepared at Caltech with financial support from the Donna and Benjamin M. Rosen Bioengineering Center.

This lesson was generated from an Jupyter notebook. You can download the notebook here.

Keeping track of all of the changes in your project over time is good practice. How many times have you edited something in something you were writing and then wanted to go back and see what you had in the first place? Wouldn't it be great to know what changes you made and when you made them?

A version control system facilitates this process of keeping track of changes over time. Beyond that, it allows multiple people to collaborate and work on parts of the same project simultaneously.

There are many version control systems. The four most prominent, in order of age, oldest to youngest, are CVS, Subversion, Git, and Mercurial (the first version of Git was released about two weeks before Mercurial, so they are really the same age). Today, Git dominates.

Git was developed by Linus Torvalds, the person who developed the Linux operating system. He named Linux after himself, and he decided to also name Git after himself ("git" is British slang for a stupid person). Try typing

man git

on the command line and read what the NAME of the software is.

Using Git as a version control system allows communication with remote repositories such as GitHub or Bitbucket. Both services provide university-affiliated people with a .edu email address with perks that include free private repositories. We will use GitHub for our bootcamp, and you should already have set up an account.

Remote repositories are not only a great way for keeping your data safe. They are also an excellent tool for collaboration since Git allows multiple users to edit the shared files simultaneously and has a method to merge changes afterwards. Public repositories can also serve as a vehicle to distribute code (or other files).

You can find more information about Git here. It is well documented. Here is an excellent one-page (front-and-back) cheatsheet.

Let's get started. You all should have a version of Git installed on your computers. Open the terminal and navigate into your ~/git directory.

Configuring Git¶

While you already used Git in lesson 0, you still have some configuring to do. For this, and everything else in the tutorial, we'll use the command line. We will do the configuration with --global flags, which means these specifications work for all of your repositories. First, we'll specify the name and email address of the person working with Git on your machine (that's you!).

git config --global user.name "YOUR NAME"

git config --global user.email "YOUR EMAIL ADDRESS"

Git is very well documented and help is easily available. If you need to know more about config, for example, just enter:

git help configCloning Repositories¶

You have already cloned the bootcamp repository in lesson 0. We'll practice that again here, and clone one of the zillions of public repositories that are hosted on GitHub. We will clone a simple package, called insulter that will hurl Shakespearean insults at you.

git clone https://gist.github.com/3165396.git insulter

Note that the insulter package is now on your machine. You have a copy of it on your own hard drive. You do not need to be connected to the internet to use it.

Now, cd to insulter and you can start using it, thou wayward tickle-brained flap-dragon!

python insulter.pyPulling in changes¶

Actively developed repositories are constantly being updated. After you clone the repository, its authors may add or edit things in the repository. For you to get those changes, you need to fetch them and then merge them into what you have locally.

To fetch the updated repository, you guessed it, you do:

git fetch

The result is stored in a hidden directory, .git/FETCH_HEAD. (Directories that begin with a . are hidden; you don't see them when you type ls.)

Now that there are changes, you would like to update your local repository. Provided you do not have any local edits, this is seamless. You just do

git merge FETCH_HEAD

Now your repository will be up to date.

A shortcut for the commands

git fetch

git merge FETCH_HEAD

run in succession is

git pull

In practice, you will use this a lot, but, as you will see, we will use fetching and merging on a forked repository in the next lesson, so it can be useful.

Let's try doing this with the bootcamp repository. cd into ~/git/bootcamp/. Now, type

git pull

This will "pull" in any changes make to the repository. Throughout the bootcamp, we may need to update files in the repository, so you may need to git pull throughout the bootcamp.

Note that git pull is actually shorthand for

git pull origin master

which is the more verbose way of saying that you want to pull the master branch from the remote repository named origin. We will not discuss branching in this bootcamp, but it is an important concept to learn about.

Generally it is good practice to pull before you start working each day to make sure you pull in any updates your collaborators may have made.

Pulling in changes from an upstream repository¶

As you saw in lesson 0, it is sometimes useful to pull from an upstream repository. In lesson 0, you added an upstream remote repository to the bootcamp repository. To pull from the upstream repository, you need to use the more verbose version of git pull.

git pull upstream masterCreating your own repository¶

Now, you will create your own repository for practice. For this bootcamp, let's name the repository with your initials followed by _bootcamp. In my case, my repository is jb_bootcamp.

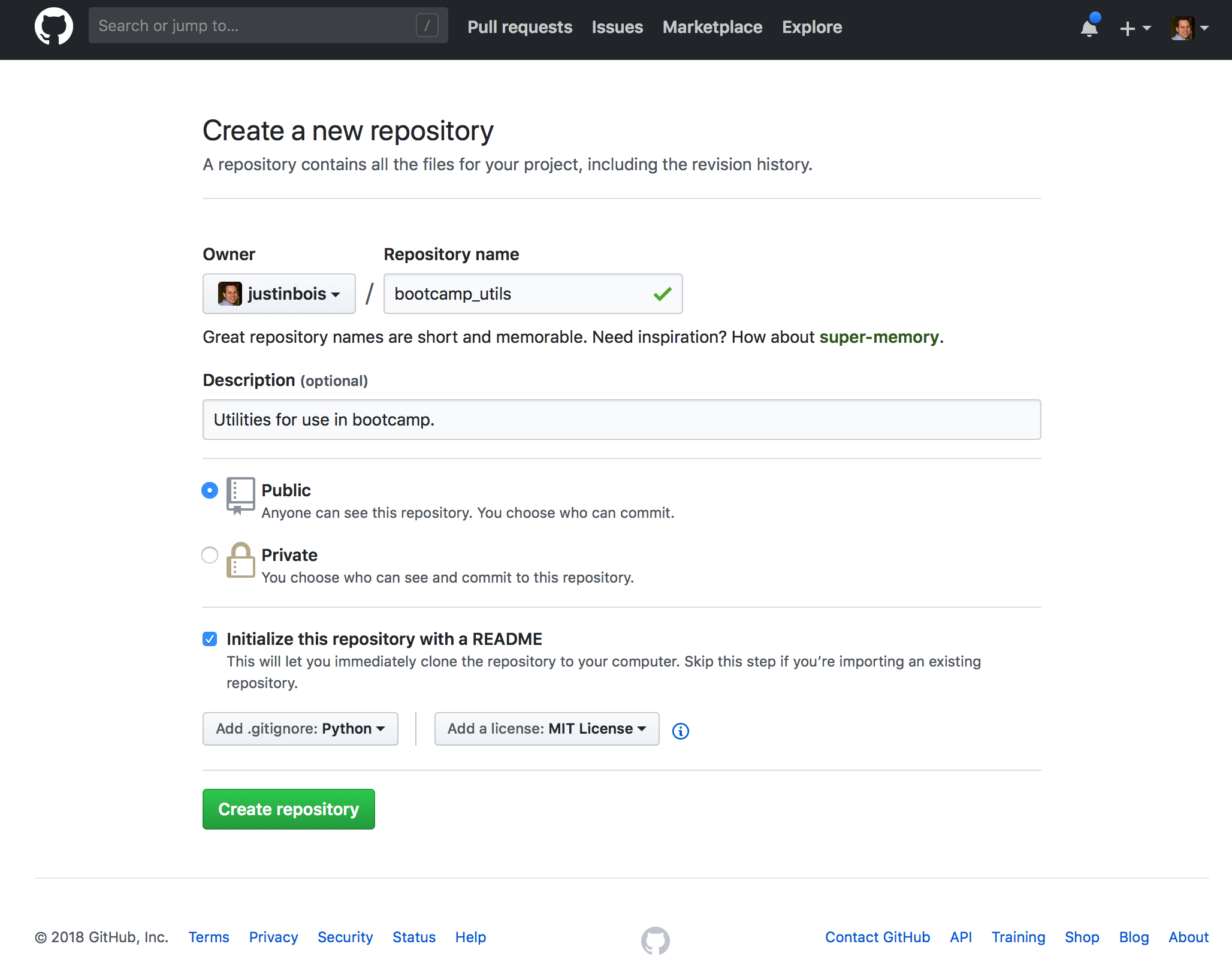

Only in rare circumstances would you not want to host your repository remotely, so we will take an easy path toward creating a repository using GitHub. Prior to the bootcamp, you all should have set up a GitHub account. Log in to GitHub. In the upper right corner of the page, click on the "+" icon and select "New repository." You will then get a page that looks like this:

I called the new repository jb_bootcamp (yours will obviously have your own initials, and you can substitute them for jb wherever you see that in this lesson), and gave a little description. You can choose the repository to be either private of public; if you are not an academic, you have to pay for private repositories. Public repositories can be viewed by anyone. I will choose public for this one.

I have checked the box to initialized the repository with a README. This is convenient because GitHub will set up the repository and populate it with a README file that you can generate right in your browser. I also selected to add a Python .gitignore, which is convenient for keeping your version control clean (more on that later). Finally, I chose an MIT license, which is a liberal license that will let others use your code if they would like to.

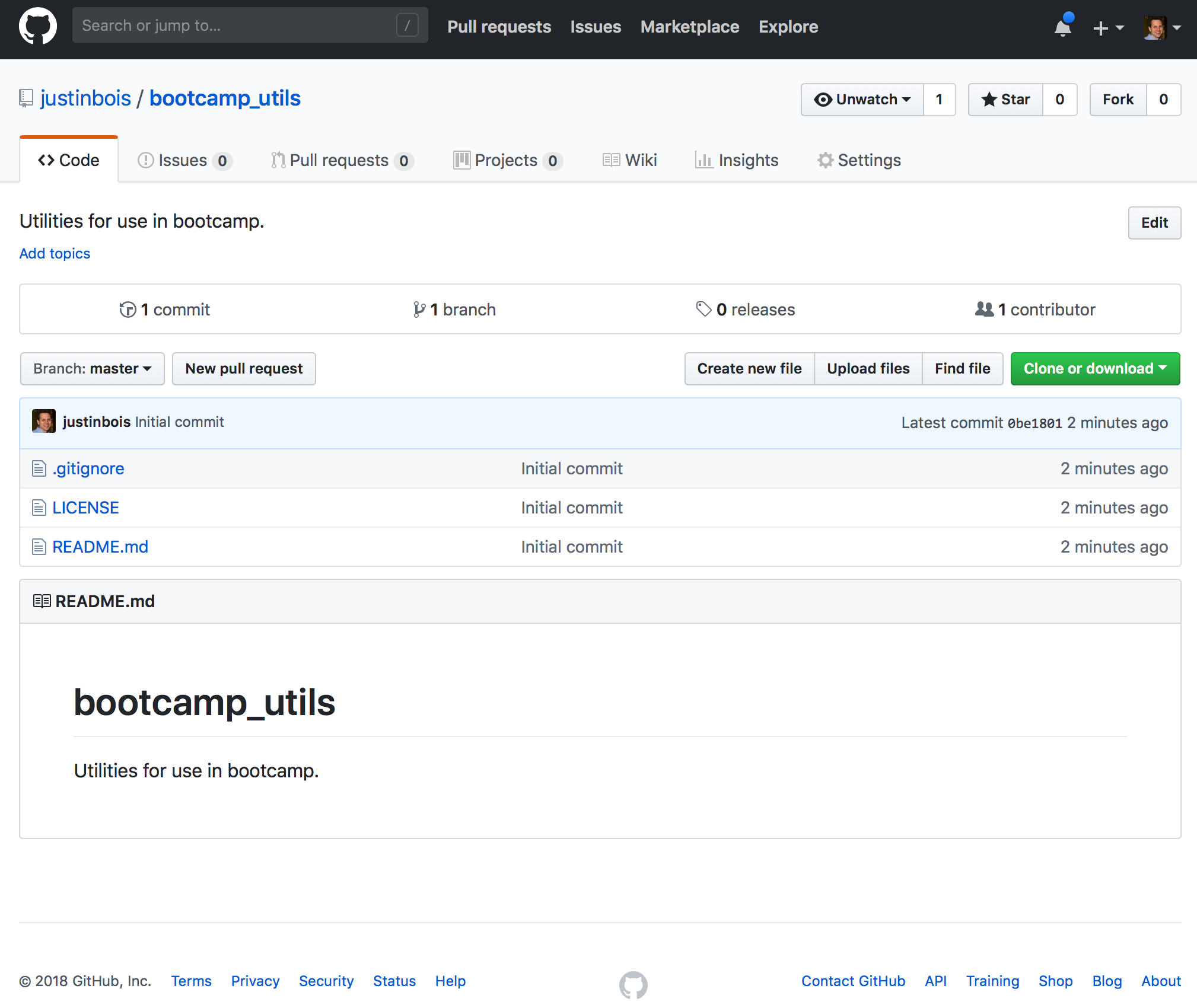

After clicking "Create repository," you will get a page that looks like this:

This is the main page for your repository. It is created! Right now, the repository only exists on GitHub. You need to clone it to get it on your own machine. To do that, click the "Clone or download" button and copy the web URL.

Now, it is time to clone your repository on your own machine. I think you know the drill. First, cd to your ~/git directory (if that is where you choose to keep your repositories). Then do this:

git clone the_url_you_just_copied

If you now cd into the jb_bootcamp directory, you can see the README.md and LICENSE files there.

Adding files to your repository¶

Now, let's update the repository. We will add the package we built in the last lesson. Conveniently, I already included its contents in the directory ~/git/bootcamp/modules/jb_bootcamp/. Copy the contents of the ~/git/bootcamp/modules/jb_bootcamp/ directory and into the ~/git/jb_bootcamp/ directory. On my machine, this is accomplished by:

cd ~/git/bootcamp/modules/jb_bootcamp/

cp -r * ~/git/jb_bootcamp/

This instructs the operating system to copy all of the contents of ~/git/bootcamp/modules/jb_bootcamp/ to your new repository. (The * is a wildcard character, which means every file in this case.) We verify that it is there by cd-ing into the new repository and typing ls.

cd ~/git/jb_bootcamp/

ls

So, it is in the repository, right? Let's ask Git. git status is a useful command that checks what is in the repository and in your working directory on your machine, and let's you know the status of all files and directories.

git status

The output looks like this:

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: README.md

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

jb_bootcamp/

setup.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")It tells us that because we copied over the README.md, the README.md file that was in the repository when you created it on GitHub has been modified. It further says that the contents of the directory jb_bootcamp/ and the file setup.py are not under version control, even though they exist in the directory that is under version control.

Before proceeding, you should change the files setup.py and jb_bootcamp/__init__.py to have your name, package name, contact information, etc., instead of mine.

Now, we need to explicitly tell Git which files need to be tracked. We also need to tell it that we want to add the modified README.md file to the repository. We do this using the git add command.

git add jb_bootcamp

git add setup.py

git add README.md

We have now added what we needed, so we have changed the repository.

Committing and pushing changes¶

Now, if we type git status, we get updated information.

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: README.md

new file: jb_bootcamp/__init__.py

new file: jb_bootcamp/bioinfo_dicts.py

new file: jb_bootcamp/na_utils.py

new file: setup.pyIt tells use we have new files and a modified file. It says these are part of "Changes to be committed." A commit is essentially a revision of a repository. It marks a point in the development of the repository that you want to mark. So, let's commit the present state of the repository.

git commit -m "Initial commit of bootcamp utilities."

The -m after git commit specifies the commit message. This is a brief bit of text that describes what has changed in the repository. Upon committing, the something like the following is printed to the screen:

[master 27aba6d] Initial commit of bootcamp utilities.

5 files changed, 120 insertions(+), 1 deletion(-)

create mode 100644 jb_bootcamp/__init__.py

create mode 100644 jb_bootcamp/bioinfo_dicts.py

create mode 100644 jb_bootcamp/na_utils.py

create mode 100644 setup.pyThe number 27aba6d (yours will be different) is the short version of the commit identifier. If you ever want to go back to a previous version of the repository, this identifier will be a great help.

Now, the commit is still only on your local machine. In order for your collaborators (or the whole world, if it is a public repo) to have access to it (and in order for it to appear on GitHub), you need to push it. To do that, we do this:

git push origin master

Here, origin is a nickname for your remote repository. master is the name of the branch we are pushing to in the GitHub repository. I.e., it is the master copy. (We will not talk about branches or branching in this lesson.)

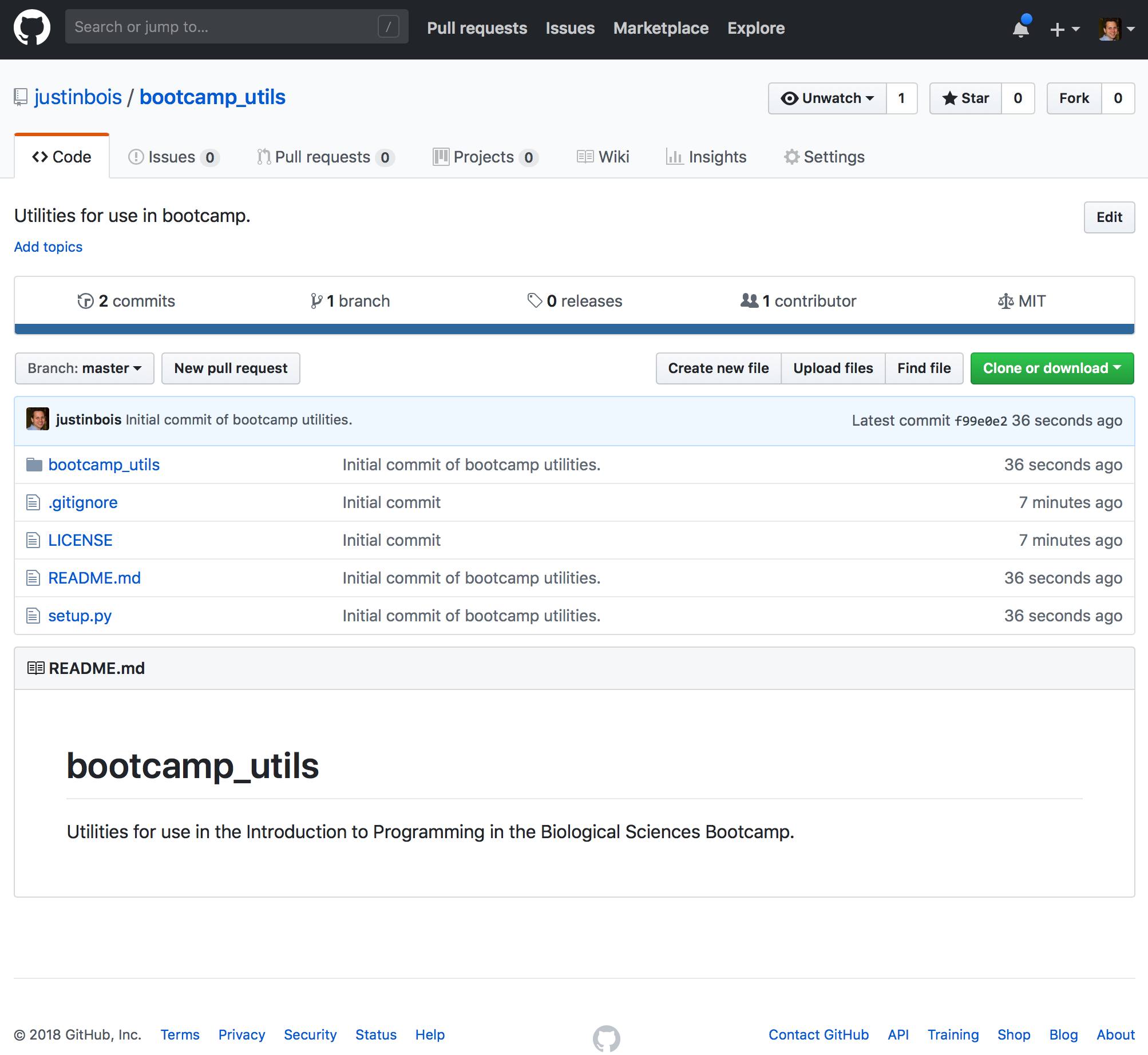

Now, let's look at our repository on GitHub. You can just refresh the main page of the repository in your browser. It now looks like this:

We now have our updates in the master branch, out there in the cloud for sharing.

.gitignore¶

Notice that before you added the files to your repository, Git let you know that there was an untracked file in your directory. Sometimes you do want to have files in the directories of your repository, but not keep those files under version control. Examples of these might be binary files, large data sets, images, etc.

Fortunately, you can tell Git to ignore certain files. This is done using a .gitignore file. Each line of of the .gitignore file says which files to ignore. For example, to ignore all files that end with .tif, you would include the line

*.tif

in your .gitignore file. The * is a wildcard character which says to ignore all files that have a file name ending with .tif, regardless of what the prefix is. Now, whenever you you use git status, any file ending with *.tif that happens to be on your machine within the directories containing your repository will be ignored by Git.

Just because *.tif appears in a .gitignore file does not mean that all .tif files will be ignored. If you explicitly add a file to the repository, Git will keep track of it. E.g., if you did

git add myfile.tif

then myfile.tif will be under version control, even if other .tif files laying around are not. (Note, though, that you typically do not want to have binary files under version control. You typically only keep code under control. Typically only data sets used to test code are included in the repository. Version control is not really for data, but for code.)

Finally, since it begins with a .. When you put a .gitignore file in a directory, the .gitignore file will not show up when you run ls at the command line without the -a flag.

Installing your package¶

To install your package, you use pip, which is a self-referential acronym Pip Installs Packages. To install a your package, make sure you are in the directory immediately above your package, in this case ~/git. Then, do the following on the command line.

pip install -e jb_bootcamp

The -e flag is important, which tells pip that this is a local, editable package.

Your package is now accessible on your machine whenever you run the Python interpreter!