Lesson 18: Python style¶

(c) 2019 Justin Bois. With the exception of pasted graphics, where the source is noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0. All code contained herein is licensed under an MIT license.

This document was prepared at Caltech with financial support from the Donna and Benjamin M. Rosen Bioengineering Center.

This lesson was generated from a Jupyter notebook. You can download the notebook here.

%load_ext blackcellmagic

import numpy as np

This lesson is all about style. Style in the general sense of the word is very important. It can have a big effect on how people interact with a program or software. As an example, we can look at the style of data presentation.

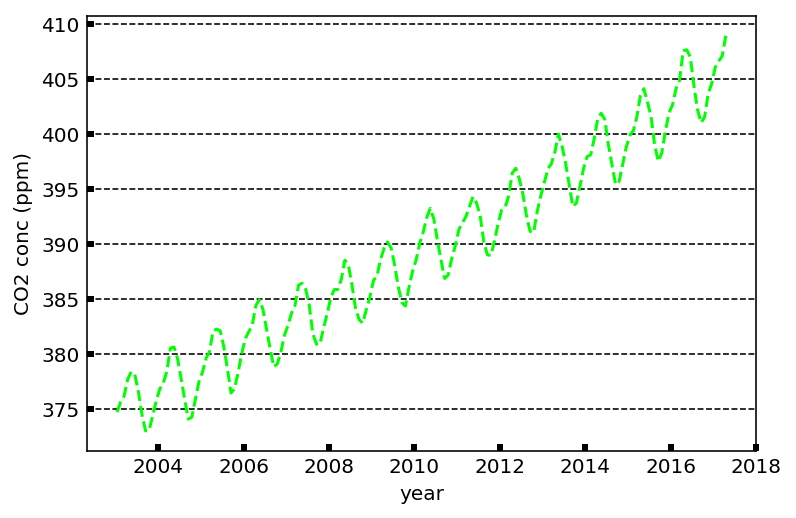

The Keeling curve is a measure of the carbon dioxide concentration on top of Muana Loa over time. Let's look at a plot of the Keeling curve.

I contend that this plot is horrible looking. The green color is hard to see. The dashed curve is difficult to interpret. We do not know when the measurements were made. The grid lines are obtrusive. Awful.

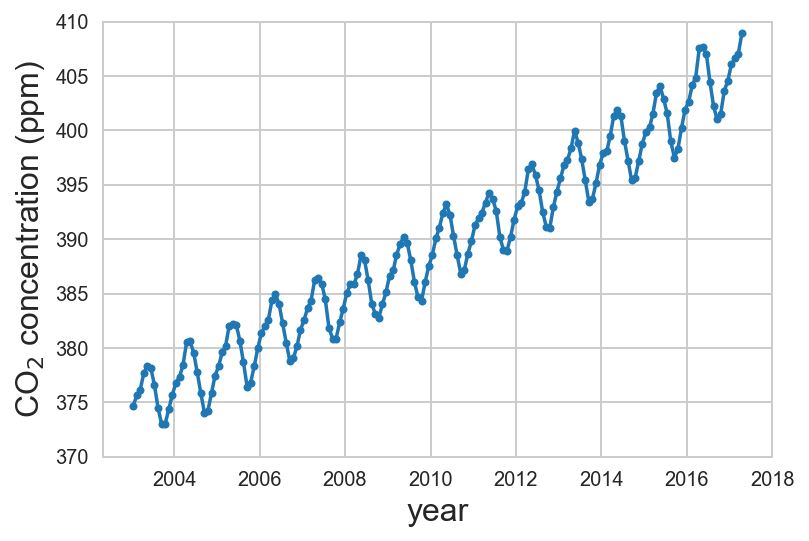

Lest you think this plot is a ridiculous way of showing the data, I can tell you I have seen plots just like this in the literature. Now, let's look at a nicer plot.

Here, it is clear when the measurements were made. The data are clearly visible. The grid lines are not obtrusive. It is generally pleasing to the eye. As a result, the data are easier to interpret. Style matters!

(We will talk about how to make beautiful plots like the one here later in the bootcamp.)

The same arguments about style are true for code. Style matters! We already discussed how important documentation is, but having a well-defined style also helps keep your code clean, easy to read, and therefore easier to debug and share.

Coding style in general and Future You¶

The book, The Art of Readable Code by Boswell and Foucher is a treasure trove of tips about writing well-styled code. At the beginning of their book, they state the Fundamental Theorem of Readability.

Code should be written to minimize the time it would take for someone else to understand it.

This is in general good advice, and this is the essential motivation for using the suggestions in PEP8. Before we dive into PEP8, I want to introduce you to the most important person in the world, Future You. When you are writing code, the person at the front of your mind should be Future You. You really want to make that person happy. Because as far as coding goes, Future You is really someone else, and you want to minimize the time it takes for Future You to understand what Present You (a.k.a. you) did.

PEP 8¶

Guido van Rossum was the benevolent dictator for life (BDFL) of Python. He stepped down in July of 2018. Until that time, to get new features or other enhancements into the language, Guido either writes or (usually) considers a Python Enhancement Proposal, or a PEP. Each PEP is carefully reviewed, and often there are many iterations with the PEP's author(s). Ultimately, Guido decided if the PEP becomes part of the Python language. Now, that decision is made by the Python Steering Council, which consists of five members.

Perhaps the best-known PEPs are PEP 8 and PEP 20. This lesson is about PEP 8, but we'll pause for a moment to look at PEP 20 to understand why PEP 8 is important. PEP 20 is "The Zen of Python." You can see its text by running import this.

import this

These are good ideas for coding practice in general. Importantly, beautiful, simple, readable code is a goal of a programmer. That's where PEP 8 comes in. PEP 8 is the Python Style Guide, written by Guido, Barry Warsaw, and Nick Coghlan. You can read its full text in the Python PEP index, and I recommend you do that.

Some people recommend following PEP 8 to the letter, but a prevailing opinion is that PEP 8 should serve as a guide, and its rules may be bent or broken if that aids clarity. Even if you view them as guidelines, you should only stray from them when it is really necessary. Trust me; my life got much better after I started following PEP 8's rules.

Note, though, that your code will work just fine if you break PEP 8's rules. In fact, some companies have their own style guides. Google has its own style, with its old style being deprecated and replaced by a much more PEP8 adherent style.

Key points of PEP 8¶

PEP 8 is extensive, but here are some key points for you to keep in mind as you are being style-conscious.

- Variable names need to be descriptive.

- Variable names are all lower case with underscores separating words.

- Do not name variables

l,O, orIbecause they are hard to distinguish from ones and zeros. - Function names are lower case and may use underscores.

- Class names are in PascalCase, where every word in the name of the class has the first letter capitalized and there are no spaces between words. (We are not explicitly covering classes in the bootcamp, though we did in the past. You will come across PascalCase objects in other packages, which usually means you are instantiating a class.)

- Module names are short and lower case. Underscores should be avoided unless necessary for readability.

- Lines are maximally 79 characters long.

- Lines in doc strings are maximally 72 characters long.

- Avoid in-line comments; put the comment directly above the code.

- Avoid excessive comments that state the obvious.

- Generally, put single spaces around binary operators, unless omitting space improves readability. For example,

x**2 + y**2. Low precedence operators should have space. - Assignment operators should always have single spaces around them except when in keyword arguments. E.g., no space in

f(x, y=4). - Put spaces after commas in function definitions and calls. This also applies for lists, tuples, NumPy arrays, etc.

- Avoid excessive spaces within parentheses, braces, and brackets.

- Use a single blank line to separate logical sections of your code.

- Put two blank lines between functions in a

.pyfile. - Put all import statements at the top of the file, importing from one module per line.

Perhaps the rule that is bent the most is the line width rule (but do not break the line width rule for doc strings!). Sometimes, it is better to avoid a line break for clarity, but very long lines are a big no-no!

Some examples of PEP 8-ified code¶

Let's now look at some examples of code adhering to PEP 8 and code that does not. We'll start with some code we used before to find start codons.

seq='AUCUGUACUAAUGCUCAGCACGACGUACG'

c='AUG' # This is the start codon

i =0 # Initialize sequence index

while seq[ i : i + 3 ]!=c:

i+=1

print('The start codon starts at index', i)

Compare that to the PEP 8-ified version.

start_codon = 'AUG'

# Initialize sequence index for while loop

i = 0

# Scan sequence until we hit the start codon

while seq[i:i+3] != start_codon:

i += 1

print('The start codon starts at index', i)

The descriptive variable names, the spacing, the appropriate comments all make it much more readable.

Here's another example, the dictionary mapping single-letter residue symbols to the three-letter equivalents.

aa = { 'A' : 'Ala' , 'R' : 'Arg' , 'N' : 'Asn' , 'D' : 'Asp' , 'C' : 'Cys' , 'Q' : 'Gln' , 'E' : 'Glu' , 'G' : 'Gly' , 'H' : 'His' , 'I' : 'Ile' , 'L' : 'Leu' , 'K' : 'Lys' , 'M' : 'Met' , 'F' : 'Phe' , 'P' : 'Pro' , 'S' : 'Ser' , 'T' : 'Thr' , 'W' : 'Trp' , 'Y' : 'Tyr' , 'V' : 'Val' }

My god, that is awful. The PEP 8 version, where we break lines to make things clear, is so much more readable.

aa = {'A': 'Ala',

'R': 'Arg',

'N': 'Asn',

'D': 'Asp',

'C': 'Cys',

'Q': 'Gln',

'E': 'Glu',

'G': 'Gly',

'H': 'His',

'I': 'Ile',

'L': 'Leu',

'K': 'Lys',

'M': 'Met',

'F': 'Phe',

'P': 'Pro',

'S': 'Ser',

'T': 'Thr',

'W': 'Trp',

'Y': 'Tyr',

'V': 'Val'}

For a final example, consider the quadratic formula.

def qf(a, b, c):

return -(b-np.sqrt(b**2-4*a*c))/2/a, (-b-np.sqrt(b**2-4*a*c))/2/a

It works just fine.

qf(2, -3, -9)

But it is illegible. Let's do a PEP 8-ified version.

def quadratic_roots(a, b, c):

"""Real roots of a second order polynomial."""

# Compute square root of the discriminant

sqrt_disc = np.sqrt(b**2 - 4*a*c)

# Compute two roots

root_1 = (-b + sqrt_disc) / (2*a)

root_2 = (-b - sqrt_disc) / (2*a)

return root_1, root_2

And this also works!

quadratic_roots(2, -3, -9)

Line breaks¶

PEP8 does not comment extensively on line breaks. I have found that choosing how to do line breaks is often one of the more challenging aspects of making readable code. The Boswell and Foucher book spends lots of space discussing it. There are lots of considerations for choosing line breaks. One of my favorite discussions on this is this blog post from Trey Hunner. It's definitely worth a read, and is about as concise as anything I could put here in this lesson.

Black¶

I have recently found Black to be a very useful tool for style. It's self-ascribed adjective is "uncompromising." Black does not pay any attention at all to the formatting you chose, but will apply its style to your code. It adheres quite closely to PEP 8, with one of the most notable differences being a default line width of 88 characters. Code that is formatted using Black is said to be "blackened."

You can install Black on the command line with pip:

pip install black

There is also a magic function that can blacken code cells in Jupyter notebooks. You can also install that with pip.

pip install blackcellmagic

To use Black to format a cell after installing blackcellmagic, you simply put %%black at the top of the cell. Of course, you have to first load the Black extension using %load_ext blackcellmagic, which I did in the import cell at the top of this notebook.

When you put %%black at the top of a cell and execute the cell, the code is reformatted and the %%black text disappears. Very slick! You do need to execute the cell again after it is reformatted, though, to have the code run.

Below is what I get when I execute a code cell that had our ugly code from before with %%black.

Before:

%%black

seq='AUCUGUACUAAUGCUCAGCACGACGUACG'

c='AUG' # This is the start codon

i =0 # Initialize sequence index

while seq[ i : i + 3 ]!=c:

i+=1

print('The start codon starts at index', i)

After:

seq = "AUCUGUACUAAUGCUCAGCACGACGUACG"

c = "AUG" # This is the start codon

i = 0 # Initialize sequence index

while seq[i : i + 3] != c:

i += 1

print("The start codon starts at index", i)

Note the Black switched from single quotes to double quotes and put spaces around the operators. However, it did not mess with comments, as it tends not to do that. Let's see what happens when we blacken our PEP 8 adherent version of that code.

Before:

start_codon = 'AUG'

# Initialize sequence index for while loop

i = 0

# Scan sequence until we hit the start codon

while seq[i:i+3] != start_codon:

i += 1

print('The start codon starts at index', i)

After:

start_codon = "AUG"

# Initialize sequence index for while loop

i = 0

# Scan sequence until we hit the start codon

while seq[i : i + 3] != start_codon:

i += 1

print("The start codon starts at index", i)

Black liked must of what we did, but it changed the spacing in our slicing of seq. I personally do not like this choice by Black, but Black is strictly adhering to PEP 8 on this.

This is really important.¶

I want to reiterate how important this is. Most programmers follow these rules closely, but most scientists do not. I can't tell you how many software packages written by scientists that I have encountered and found to be almost completely unreadable. Many of your colleagues will pay little attention to style. You should.

Computing environment¶

%load_ext watermark

%watermark -v -p numpy,black,jupyterlab